The ‘Mental Health Toolkit for Veterans (MeT4VeT)’ Project – Is There a Role for Apps in Veterans’ Mental Health?

Mobile health apps have flooded the market in recent years with as many as 325,000 available in 2017 (Research2Guidance, 2017). They have many benefits such as accessibility, low cost and the appeal of anonymity and are actively encouraged by the World Health Organisation (2012). Even before the Covid-19 pandemic forced many services to offer online services, King’s Centre for Military Health Research was beginning to investigate whether mobile phone apps could be utilised to help the UK Armed Forces.

Previous research by Rafferty et al. (2020) explored why veterans are unlikely to seek help for mental health problems. Their study identified three core barriers to help-seeking: define, recognise, and support. Firstly, veterans described not being able to define and identify what they were experiencing as a mental health problem. For example, they were able to recognise changes in their temper but were not able to identify this as a mental health issue.

The authors suggested that being able to identify mental health issues was an important precursor to engaging with support. Secondly, veterans often failed to recognise the need to seek help for their mental health before they reached a crisis point or a family member suggested they sought help. Finally, once they were ready to seek help, they were overwhelmed with the plethora of services available ranging from the NHS to the third sector. They also had difficulty understanding which services they were eligible for and could have access to.

The ‘Mental Health Toolkit for Veterans (MeT4VeT)’ project aimed to develop a toolkit to help veterans overcome these barriers. A key element of the project was to co-produce it with veterans and for veterans, their family members, and stakeholders to be involved in the process. We held several workshops at different stages of the project. One of the first findings of those workshops was the view that an app format would be very beneficial. The main reasoning was that an app would allow anonymity. As the app would be targeted at those who had not yet sought help, it was recognised that many may still feel shame and stigma and so an app would allow them to privately reflect on their mental health without the need to seek support yet.

What does it look like?

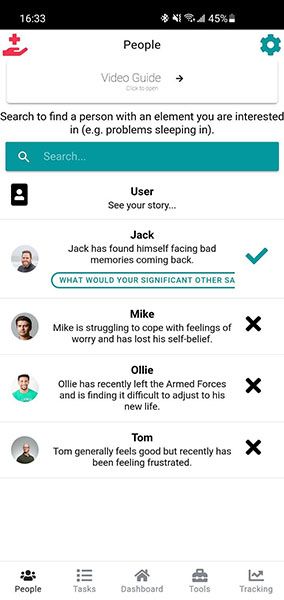

The workshops with veterans helped us to shape the app and we hope it is clear from the final product that the feedback and discussions we had with veterans were the driving force behind its features. There are five core elements of the app:

- People

- Tasks

- Tools

- Tracking

- Signposting

The user journey through the app can be summarised as follows. Firstly, the app asks the user to listen to four individuals speaking about their experience of mental health (stories are amalgamations of real experiences and spoken by actors). From those stories, the app highlights different thoughts, feelings and behaviours and asks users to differentiate between them.

They are then asked which thoughts, feelings, and behaviours they relate to in an effort to persuade them to reflect on their own experience. Once the user has created their own ‘story’, they are encouraged to set tasks (based on behavioural activation) to work on their behaviours. For example, if a behaviour is “I don’t socialise anymore” then it would assist users in creating a stepwise approach to improve this.

The Tools section is used to work on the user’s thoughts and feelings. These tools were kindly shared with us by Public Health England and are from the Every Mind Matters resource (NHS, 2021)and include tools such as reframing negative thoughts and breathing exercises. Each week, users are asked to check in to record how their thoughts, feelings and behaviours are changing. If they report they are getting worse, they are prompted to look at the list of resources and it is suggested that they may benefit from seeking formal treatment.

Does it work?

We are currently running a feasibility trial to see if the app is acceptable and gather initial feedback on the app. If this is something that veterans find useful, we will aim to conduct a randomised control trial to assess its impact on help-seeking and mental health symptoms. If you would like more information, please contact us: [email protected].

This article was first published in the QNVMHS newsletter. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/ccqi/quality-networks-accreditation/qnvmhs/publications

This study has been funded by the the Forces in Mind Trust.

Sources:

- NHS. Every Mind Matters. (2021) https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/.

- World Health Organization. (2012). National eHealth strategy toolkit. https://www.who.int/ehealth/publications/overview.pdf

- Rafferty, L. A., Wessely, S., Stevelink, S. A. M., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The journey to professional mental health support: A qualitative exploration of the barriers and facilitators impacting military veterans’ engagement with mental health treatment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1700613

- Research2Guidance. (2017). 325,000 mobile health apps available in 2017—Android now the leading mHealth platform. https://research2guidance.com/325000-mobile-health-apps-available-in-2017/.