Increase in PTSD among UK veterans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq – new research

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has increased among the UK’s armed forces in the last ten years, our latest research shows. We have been following military service men and women since 2003 in one of the largest ongoing studies of its kind in the UK. Our work explores the potential impact of serving in Iraq and Afghanistan on the health and well-being of UK military personnel.

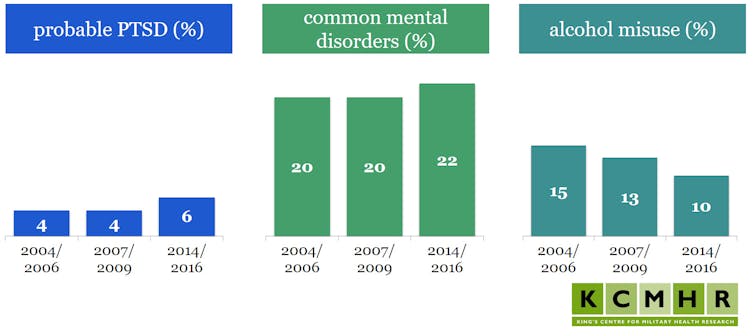

Results from two earlier phases (in 2004-2006 and 2007-2009) have already been published. Outcomes from the latest phase of our study, based on data gathered from over 8,000 military personnel between 2014 and 2016, tell us that the overall rate of PTSD among serving personnel and veterans is 6%, compared with 4% in the earlier two phases. While levels of PTSD in our military sample were similar to those in the general population in 2004-2006 and 2007-2009, the rates have now risen.

It’s important to note that in large-scale studies, such as this one, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, it is not possible to conduct individual clinical assessments for PTSD. Participants are considered to have the condition if they score 50 or higher on the 17-item National Center for PTSD Checklist (PCL-C), a cut-off in line with international research standards.

The rise of PTSD

The increase in PTSD was mainly seen among veterans who had served in Iraq or Afghanistan. The rate of PTSD among these veterans was 9%, compared with 5% for veterans who did not serve in Iraq or Afghanistan. About 5% of those currently serving reported symptoms of PTSD, whether they had been deployed to conflict zones or not.

For veterans, the role undertaken while deployed was associated with their risk of PTSD: 17% of veterans deployed in a combat role reported symptoms of probable PTSD, compared with 6% in a support role – for example, medical or logistical teams.

This is the first time the risk of PTSD for veterans deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan has been identified as substantially higher than the risk for those still serving. Although the increase is a concern, not every veteran has deployed, and only about one in three serve in a combat role. There is no single reason why PTSD is more common among veterans, but one possible explanation is that those who are mentally unwell are more likely to leave the armed forces.

It seems that the legacy of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan on mental health has taken time to reveal itself. But it would be wrong to say there is a “time bomb” of PTSD in the UK military and veteran community. In fact, PTSD remains less common than either alcohol misuse or common mental disorders.

Other mental health problems

Our analysis did reveal some good news: alcohol misuse has decreased, from 15% in 2004-2006 to 10% in 2014-2016. Although this rate is still much higher than the rate of 4% found among the general population.

The observed reduction is in line with a similar trend of people drinking less in the UK, but it is also possible that efforts by the armed forces to reduce alcohol consumption are beginning to pay off.

In terms of common mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, substantial rates emerged for veterans who held a combat role – 31% compared with 22% overall. However, overall rates of these disorders have not increased from previous phases.

The bottom line

Our findings suggest that the transition back to, and the maintenance of, a happy and successful civilian life may be difficult for some veterans. Leaving the service after many years in a supportive and structured environment may result in stresses that contribute to poor mental health, particularly if a veteran struggles to find housing or meaningful employment. So it’s important that research into the longer-term health repercussions of military service continues.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Opening image credit to StutterStock.