What does post-traumatic stress look and feel like for former UK Army and Royal Marine personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan?

From interviewing ex-soldiers in this study, the team discuss how difficult deployment experiences were compartmentalised quite well when people were in the military. This was due to the military’s structure, camaraderie, shared experiences and a way of explaining violence and loss. When leaving the military, some people’s post-traumatic stress from their deployments were re-triggered. We explore why this may be the case, and why people who did not experience lingering post-traumatic might be different.

What do we know already?

Previous research found that most personnel do not develop lasting mental health issues after experiencing traumatic events, but a significant minority report ongoing psychological and social difficulties, particularly after leaving the military. A UK study on current and former military personnel found an increase in probable Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)[1] among military personnel over 12 years (4-5% in 2004-9 to 6% in 2014-16), yet levels were highest for those who had served in combat roles in Iraq or Afghanistan and who had later left the military (17%) (1).

So why do people who go through very similar experiences develop PTSD or not? A concoction of factors can influence this – from difficulties in childhood through to the way that individuals build and process traumatic memories, the meaning the event takes on and how much support people can access. Little research has, however, been interested in how post-traumatic stress feels from someone who has experienced it and how it may feel like as it emerges and develops over time.

What was the study about?

The participants in this study were ex-military personnel who were deployed to the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts in combat roles – this was the group with the highest rates of PTSD in the UK study mentioned before. This study aimed to explore how post-traumatic stress is thought to develop within their lifetimes, working out when symptoms first emerged and comparing people who did and did not show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

We interviewed a total of 17 people; 10 who indicated on a screening questionnaire that they experience enough PTSD symptoms to a level of possible diagnosis and there were 7 without symptoms. Interviews were conducted between September 2019 and March 2020. The researcher looked at individuals’ reactions to life events before, during and after the military.

The majority of participants were men. Most people enlisted before they were 18 years old. The symptomatic group included more people with adverse childhood experiences, however there was evidence of childhood adversities also in the asymptomatic group. All had been deployed in ‘front-line’ roles with similar levels of exposure to combat.

What did we find?

Holding and rupture

Results showed that the possibility of post-traumatic stress developing could be down to two concepts in particular - holding and rupture:

Holding and rupture for our participants

When in the military, personnel reported a strong holding environment which met their practical and emotional needs – such as a deep sense of belonging, training and a sense of purpose. As a result, the after-shocks of difficult events (ruptures) could be managed and contained; this included combat experiences.

Leaving the military meant soldiers lost the net of the military, including the structure and familiarity that kept memories and stress from their deployments at bay. It was only when leaving the military that some participants described shocking memories, and some described feeling like combat events were happening again and were triggered by smells, sights and sounds.

How were people with and without PTSD different?

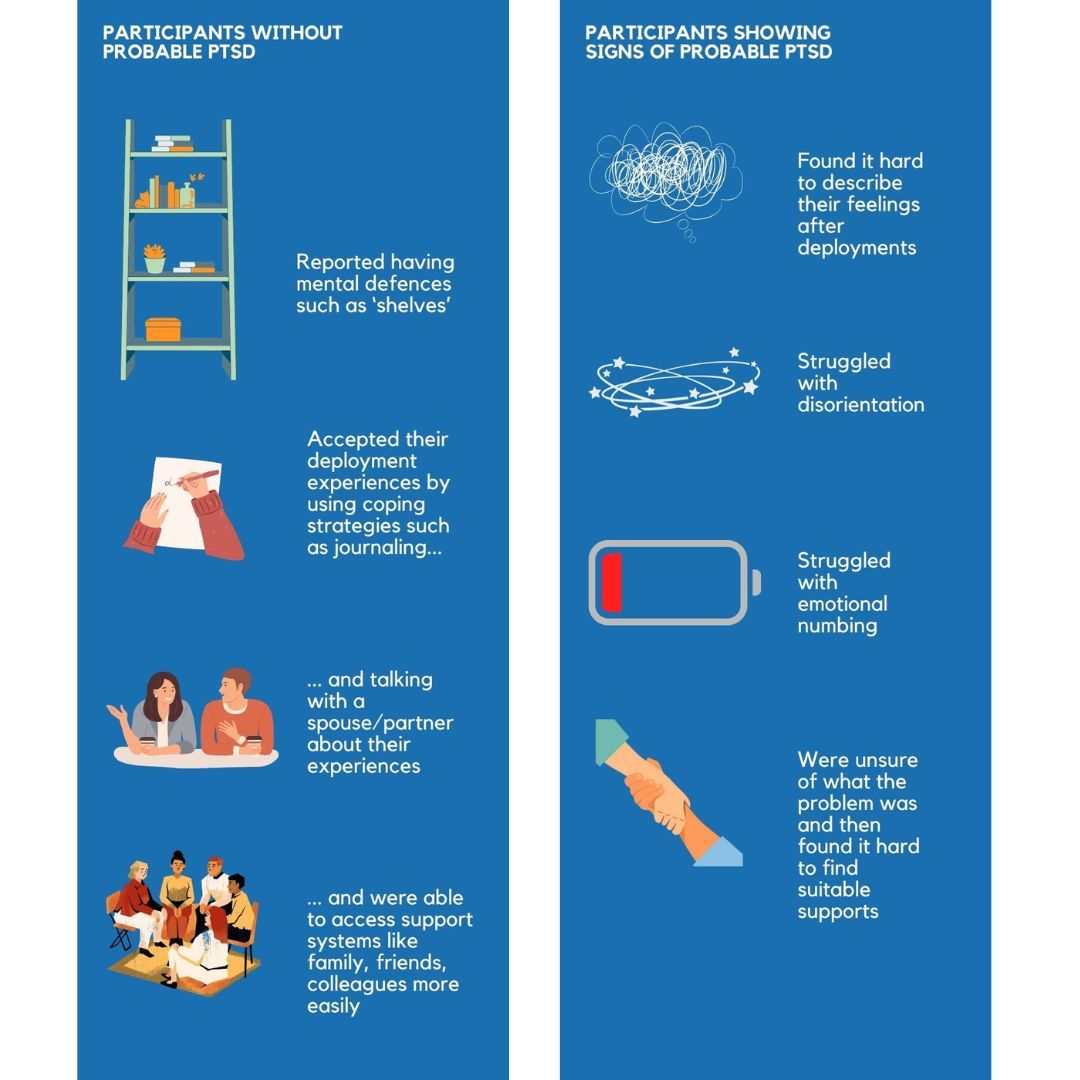

Overall, people who did not have any lingering post-traumatic stress seemed to replace some of the supports and purpose provided by the military. This included finding meaningful civilian work, hobbies and family relationships. Those with post-traumatic stress found it harder to replicate what they had in the military – made worse by their symptoms and the struggles to get the right treatment.

Although we compared those with PTSD symptoms to those without. However, we do not know if asymptomatic participants were unaffected by their deployment experiences because of the way they thought about the events, how they sought support and because they talked through their difficult experiences or – crucially - because they were not traumatised in the first place. It would be good for further studies to unpick this more.

Post-traumatic stress seemed to develop in three phases

Gathering life stories let us look at when the first symptoms reared their head and what this felt like for participants. We describe this using the concepts below:

How do we explain the results?

The main finding of this research was that post-traumatic stress from deployments seems to worsen, or re-emerge, in the years after individuals had left the military and re-joined civilian life.

We suggest three possible reasons for this:

1. The military offers a protective environment with support from peers and leadership and the military ethos and ethics. When an individual leaves, they lose their main buffer and so symptoms of PTSD start to become more obvious or are re-triggered.

2. Transitioning to civilian life can be stressful. Individuals need to find a new job, find a new social network and move their identity from soldier to civilian/veteran. PTSD symptoms may therefore ‘flare up’ in challenging times. It is possible that some symptoms are not as problematic in the military. For instance, being hypervigilant of your surroundings is necessary for survival on deployment but, in civilian life, being hypervigilant can get in the way and cause distress.

3. When an individual leaves the military, their beliefs, perspectives and ethics may change. In the military, the sense of purpose, duty and even the ideas of an ‘enemy’ can help individuals make sense of combat. When they leave the military, they may start to question, rethink or make new connections about what happened.

What are the implications?

Our findings highlighted that PTSD is not just about mental health, but involves many other holding structures like people’s employment, relationships, health, and quality of life. Treatments for PTSD must engage with the life as a whole and efforts to minimise delays and disruption in treatment are important.

Although deployment and the military-to-civilian transition mark certain moments in someone’s life, we found the impacts of these experiences can echo and link up with events over someone’s lifespan. Services supporting people after leaving the military could be aware that deployment-related trauma may reappear later on.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

Using this method to understand human experience, as opposed to statistical methods, means we understood the wider circumstances in which PTSD exists within.

We do note that our findings may not represent the experiences of all. For example, this is a small study and we did not have any officers in the PTSD symptomatic group. Officers are often from a higher socioeconomic background, have leadership responsibilities and experience the military hierarchy in a different way.

References

1. Stevelink SAM, Jones M, Hull L, Pernet D, MacCrimmon S, Goodwin L, et al. Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: a cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2018/10/08 ed. 2018;213(6):690–7.

Additional co-author: Dr Walter Busuttil